Berkeley University study of Islamophobia

in India highlights plight of Muslims

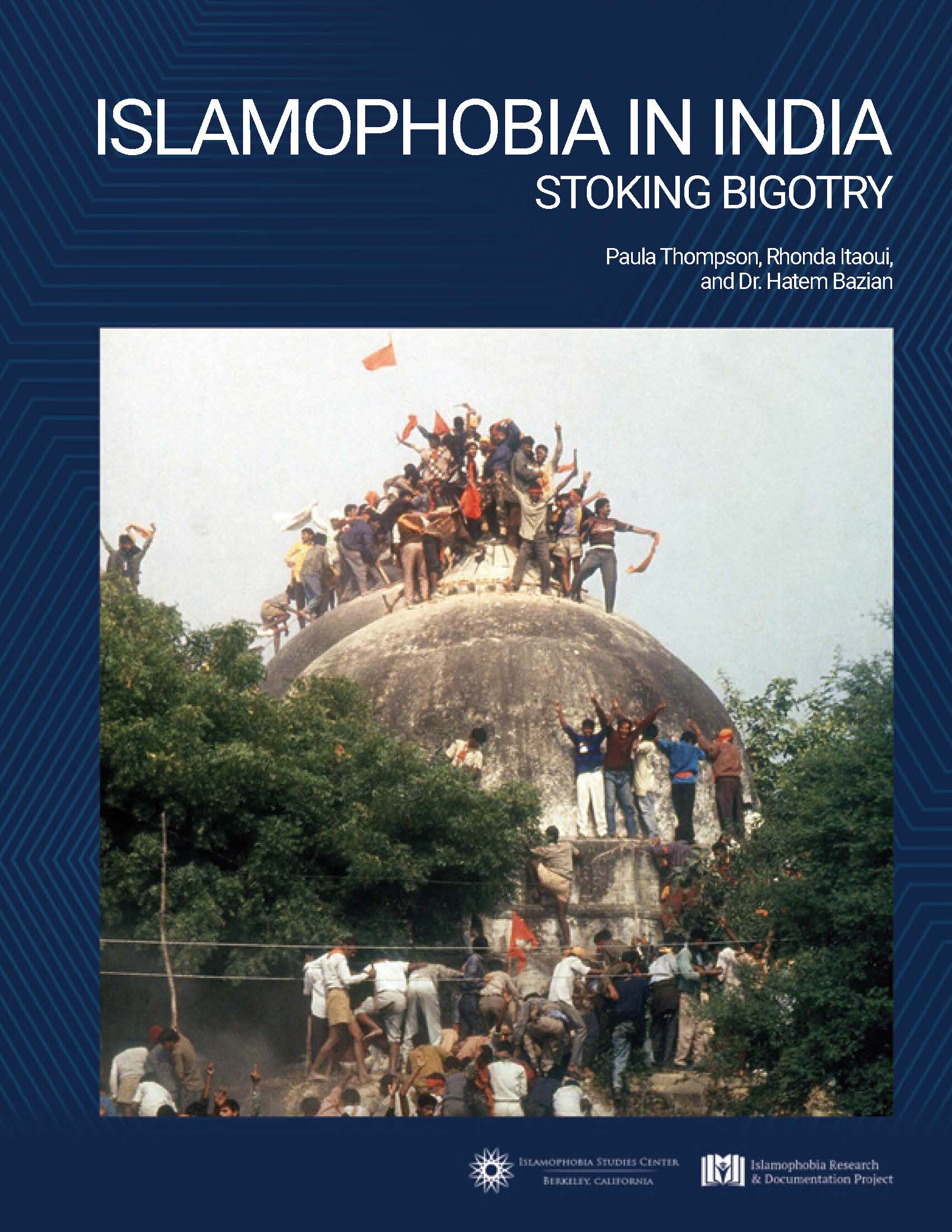

The Case of the Babri Masjid

The ancient Babri masjid was brought down by Hindu fanatics in 1992 claiming it had been built by razing a Hindu temple. The demolition of the mosque triggered nationwide communal riots claiming hundreds of lives in the following days of its demolition. This remains a ‘disputed site’, whereby both Hindus and Muslims are claiming the site for their respective religious places of worship. In 2010, the high court in the state of Uttar Pradesh, where Ayodhya is located, ruled that the mosque had been built on the ruins of a Hindu temple and ordered that the site be divided into three parcels — two for Hindu groups and the third for Muslims. Hindu and Muslim litigants have since proclaimed a division is unacceptable and emphasized the way such division further cultivates an environment of polarization and communal disharmony, for what Muslims claim is for political gain.

This violence, as well as rhetorical attacks on Muslim sites and the right to ‘be in place’ has led to greater insecurity Muslims, some of whom have recently fled areas of Uttar Pradesh on account of rising hostility. Such incidents of Islamophobia also have spatial implications on where Muslims are placed or have the right to be in place in India. This has resulted in a wide range of socio-spatial issues including the ghettoization, segregation and internal displacement of Muslims struggling to find their place in an anti-Muslim socio-political environment.

The Implications of Spatial Islamophobia: Ghettoization, Segregation and Displacement

Residential segregation along religious lines, particularly for Muslims in India has been an ongoing area of concern among scholars, human rights activists and community members, and was first brought to attention by the Sachar report that documented discrimination and socio-economic disadvantage being experienced by Muslim populations. Susewind draws attention to the way in which prolonged and unresolved histories of communal violence, and the states negligence towards Muslims has led to this large-scale ‘ghettoization’ of Muslims. On the other hand, some scholars refer to the long-standing pattern of residential clustering of Muslims in enclaves and claim that these have always been voluntary. The terms ghetto’ and ‘enclave’ are commonly used if spaces are primarily segregated along ethnic, racial, communal or caste lines.

The term ‘ghettoization’ is commonly is used to describe the impacts of politically-stoked riots, violence, and general attacks against minorities on their residential patterns and choices.526 Susewind brings attention to way in which such incidents of violence against Muslims in India have resulted in the formation of Muslim ‘ghettos’ - ‘a bounded, ethnically uniform socio-spatial formation born of the forcible relegation of a negatively typed population’. India’s Muslims are thus especially excluded from national growth by being forced to move into ghettos in order to seek refuge from physical violence. Unlike other forms of residential clustering, segregation of Muslims in urban India is thus increasingly perceived to be problematic, and commonly attributed to the state’s negligence towards this religious minority, prolonged histories of so-called ‘communal’ violence between religious groups and ensuing security concerns528 and prejudices.

The impact of politically-stoked violence on Muslim residential patterns in India is reflected in the segregated and dilapidated neighbourhoods of Juhapura in Ahmedabad and Shivaji Nagar in Mumbai, where ghettoization indeed seems to increase following each new communal riot.530 Susewind’s study similarly found that the cities where the marginalization of Muslims is understood to be primarily an outcome of communal (politically-stoked) riots are among the most highly (Ahmedabad), or moderately segregated (Mumbai and Aligarh city). Further, the negative implications of violence against Muslim communities on the spatial distribution of Muslim populations is reflected in the large-scale rural- to- urban migration following violence in Muzaffarnagar in 2013. This conflict led, to the largest internal displacement in India since Partition leaving a large number of Muslims in camps since 2013 who continue to face barriers with being resettled today.

The “ghettoization” of poor Muslims has resulted in this group being the most excluded of India’s poor from growth. This has resulted in Muslims being neglected by municipal and government authorities, failing to access water, sanitation, electricity, schools, public health facilities, banking facilities, child care centers, ration shops (subsidized public food distribution shops), roads and transport facilities within their respective residential areas.533 The increasing ghettoization of Muslims implies a shrinking space for Muslims communities in the public sphere subsequently excluding Muslims them from India’s high growth rate, whilst simultaneously isolating them from the cultural and social mainstream.

This can be connected with the Sachar Report’s findings on discrimination against Muslims in buying and renting accommodation in the locality of their choice that limits their spatial, and thus social mobility within and across various regions in India. Housing insecurity was similarly reported in the Misra Commission report which found that 34.63 percent of the Muslims lived in ‘kutcha’ (temporary) houses and 41.7 percent lived in ‘semipucca’ (semi-permanent) while the figures are 6.68 percent and 49.67 percent respectively, for the Sikhs.535 Similarly, the ratio of those living in rented houses was highest among the Muslims (43.74 percent) and among minorities, only 78.78 percent of the Muslim Households had electricity as a source of lighting as compared to Parsis (99.21 percent) and Sikhs

(88.81 percent).536 The “Disturbed Areas Act” (1991), is also a law that restricts Muslims and Hindus from selling property to each other in “sensitive” areas, was intended to avert an exodus or distress sales in neighborhoods hit by inter-religious unrest. The state, headed at the time by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, amended the law in 2009 to give local officials more power in property sales. It also extended the reach of the law, saying it was doing so to protect Muslims, who make up about 10 percent of the state’s 63 million people. However, critics see the act’s enforcement and the addition of new districts under it as state sanctioned segregation. As a result, Muslims are confined to the filthiest corners, with no hope of upliftment. Development and progress are for everyone else in the state, but not for Muslims. The division is so marked that Juhapura, a teeming township in Ahmedabad of about 400,000 people, many who moved there after the 2002 riots, is referred to by local Hindus as “Little Pakistan”. Conditions there and in other Muslim settlements in Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city, are similar, whereby residents lack proper roads, street lights, adequate drinking water, sewage pipes, and access to public clinics and schools.

Menon draws attention to the way in which rising religious tensions and violence, increasing Islamophobia and suspicion of Muslims, and the deep entrenchment and enactment of discourses of security, have pushed Muslims to seek shelter in ‘safe’ neighborhoods with large Muslim populations, such as Old Delhi.538 Muslims interviewed in Menon’s study increasingly imagine Old Delhi as a refuge, and thus consciously chose to relocate to this neighbourhood, or refuse to leave this ‘Muslim place’. Menon warns of the dangers of such ghettoization, highlighting how in the context of an exclusionary nationalism that produces boundaries which construct Muslims as the other’, Muslim containment in Old Delhi facilitates and enables easier surveillance and control by the security state. While Muslims might feel safer residing in Muslim areas, Aamr Sahib notes that schools and other institutions that would usually ensure the continuing development of these communities are moving away because of their own priorities and prejudices, further marginalizing Muslims residing in these ‘safe places’. Most interestingly, while many Muslims complained about the poor living conditions in Old Delhi, they did not necessarily view moving out of Old Delhi as an option. Exclusionary understandings of nation and belonging have ensured that it is difficult to find housing to rent or buy outside of Old Delhi if you are Muslim, highlighting the dialectic effects of Islamophobia on the segregation of Muslim communities.

The spatial impacts of Islamophobia upon Muslim sites, spaces and communities has restricted the residential options, and choices of Muslims in India. The actual and perceived threat of violence has resulted in the exclusion of Muslim communities from the national space. This has resulted in the increased ghettoization of Muslims to limited places of security and belonging that enable the survival of these communities in an increasingly hostile socio-political environment of Islamophobia. As reflected in the literature discussed in this section, such violence has negative impacts on the spatial and social mobility of Muslims in India. Such reduced mobility results in limited socio-economic opportunities to participate in national economic growth, increased housing insecurity, and an intensified geographical division of Muslims from the Hindu majority in an increasingly Islamophobic national space.

The Journal of America Team:

Editor in chief:

Abdus Sattar Ghazali

Senior Editor:

Prof. Arthur Scott

Special Correspondent

Maryam Turab

Your donation

is tax deductable.